b.Inspired

Brussels Airlines inflight magazine | February 2020

Ngamba Island: Monkeying Around

Mandi Keighran discovers how a Ugandan sanctuary for rescued chimpanzees is changing – and saving – lives.

A raucous hullabaloo is rising from the dense, green forest, ringing out over the small island on Lake Victoria in Uganda. There’s hooting, hollering, clapping, screeching and raspberry-blowing as several dozen chimpanzees come bounding and somersaulting across the grass at the forest’s edge, pushing and shoving as they make their way through a narrow walkway into a large holding area. There, they reach out their hands, some clapping, others slapping their bellies, as caretakers distribute silver bowls of porridge.

It’s mealtime on Ngamba Island (nicknamed ‘Chimp Island’), a sanctuary for 49 rescued chimpanzees, where I’ve come to learn more about humans’ closest relatives and the challenges they face as an endangered species. And, just like me, the chimps get excited when it’s feeding time. Four times a day, they return from the forest and are given fruits, vegetables and porridge, thrown from an observation deck during the day, or handed to them in bowls in the evening. It might seem like an unnatural way for these animals to live – but, due to their traumatic pasts, they are unable to be returned to the wild and this kind of human intervention is the only way to ensure their survival.

As the chimps finish their dinner, some start demanding seconds, while others politely hold out empty bowls for caretakers. Eazy – a cute, tiny, three-year-old chimp – blows bubbles in his porridge. Apparently, he’s not hungry today, having had his fill of foraged forest fruits. Watching them eat, it’s amazing just how human-like these great apes are. In fact, one of the first things I discover is that chimps share 98.7% of their DNA with humans, making them genetically closer to us than gorillas.

Ngamba Island was founded in 1998 by a number of animal welfare organisations, such as The Jane Goodall Institute and the International Fund for Animal Welfare, which drove an initiative to raise funds to purchase the land. It is now managed by the Chimpanzee Sanctuary and Wildlife Conservation Trust. “There were just 17 chimps at first, including six from the zoo in Entebbe, which was receiving many rescued chimps at that time,” says Joshua Rukundo, director of Ngamba Island. “An island like Ngamba creates a nice isolated environment where the chimps are safe – but it does have its challenges.”

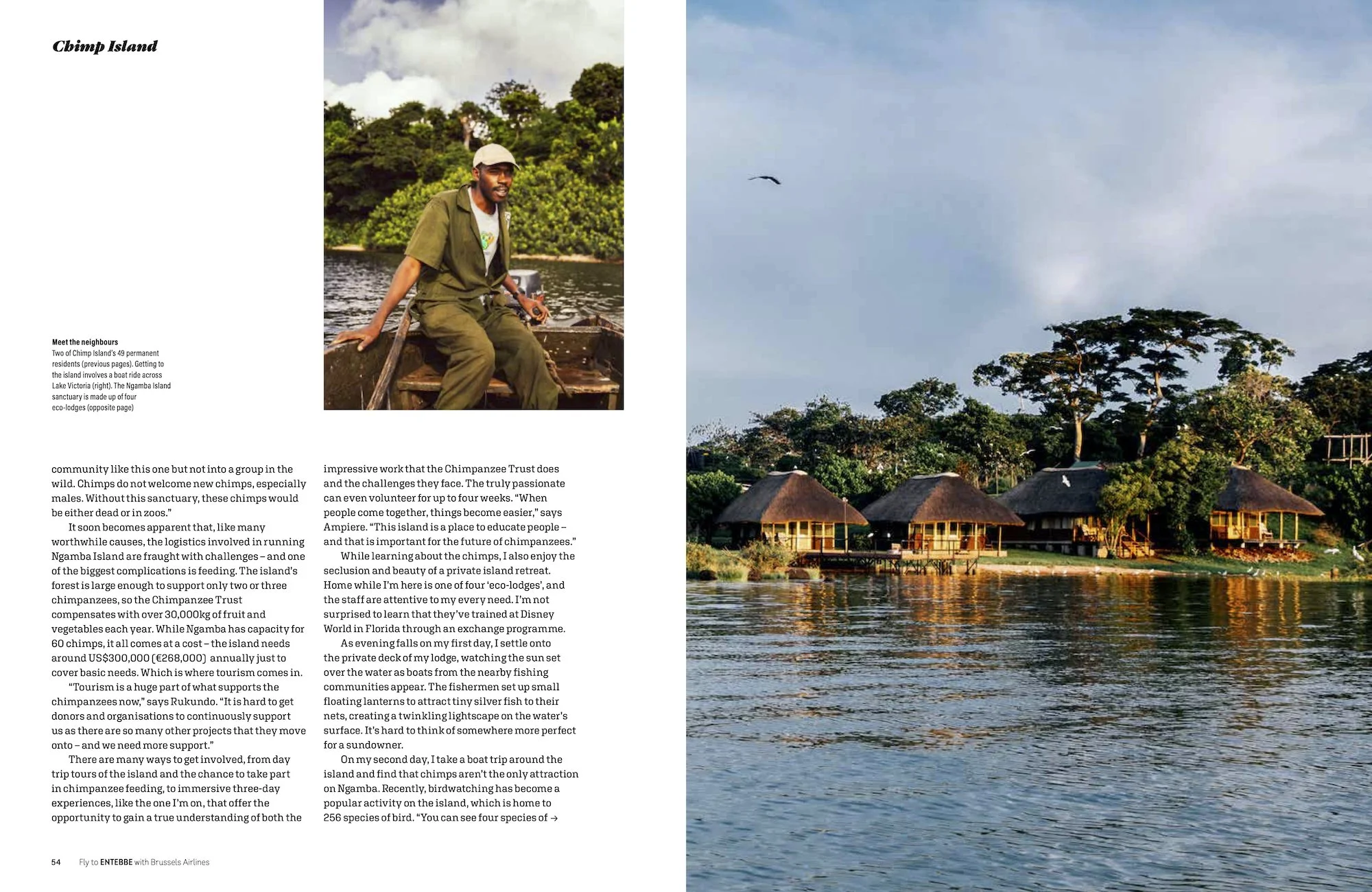

The island lies 23km south-east of Entebbe; I get there via a scenic 45-minute speedboat trip across Lake Victoria. On the way, the boat crosses the equator. It might be an invisible landmark, but it’s still a novelty, and the boat captain will happily stop for anyone who fancies a dip in the equatorial waters.

My arrival on the island is greeted by an introduction from head caregiver Innocent Ampiere and a cacophony of birdsong – most of it from the village weavers that tirelessly dart across the island collecting materials to craft their cocoon-like nests. Through the birdsong and introductions, I can hear the unmistakable sound of the island’s most famous animal population, screeching and hollering. I can’t, however, see them just yet. The 100-acre island, which looks like something out of Jurassic Park, is divided into two parts. Humans can access just five acres, while the chimps have free reign over the other 95 acres of forest, returning to a holding area on the edge of the human-inhabited part of the island for feedings and to sleep.

“It is for the safety of both the chimps and humans,” Ampiere explains. “Most of these chimps have undergone a lot of suffering and they are also

susceptible to many human diseases. Here, we have to put their welfare first.”

Indeed, the chimp’s biographies on signs by the feeding area make for difficult reading. It’s here I discover that most have been rescued from the illegal pet industry, from circuses or orphaned by the ‘bushmeat’ trade, and many come to Ngamba in horrific condition, both mentally and physically. Maisko was rescued on his way to a circus in Moscow in 1990, while Nagoti was kept locked in a cupboard before being rescued in 1999. Sunday – also known as the “boat captain” thanks to an incident involving him hijacking a fishing boat that ventured too close to shore some years ago – was castrated when he was kidnapped and sent to a circus. Others have had canine teeth removed or arrived with wounds from being tied up with rope.

“Many of these chimps have troubled pasts,” says Ampiere. “They can be integrated into a protected community like this one but not into a group in the wild. Chimps do not welcome new chimps, especially males. Without this sanctuary, these chimps would be either dead or in zoos.”

It soon becomes apparent that, like many worthwhile causes, the logistics involved in running Ngamba Island are fraught with challenges – and one of the biggest complications is feeding. The island’s forest is large enough to support only two or three chimpanzees, so the Chimpanzee Trust compensates with over 30,000kg of fruit and vegetables each year. While Ngamba has capacity for 60 chimps, it all comes at a cost – the island needs around US$300,000 (€268,000) annually just to cover basic needs. Which is where tourism comes in.

“Tourism is a huge part of what supports the chimpanzees now,” says Rukundo. “It is hard to get donors and organisations to continuously support us as there are so many other projects that they move onto – and we need more support.”

There are many ways to get involved, from day trip tours of the island and the chance to take part in chimpanzee feeding, to immersive three-day experiences, like the one I’m on, that offer the opportunity to gain a true understanding of both the impressive work that the Chimpanzee Trust does and the challenges they face. The truly passionate can even volunteer for up to four weeks. “When people come together, things become easier,” says Ampiere. “This island is a place to educate people – and that is important for the future of chimpanzees.”

While learning about the chimps, I also enjoy the seclusion and beauty of a private island retreat. Home while I’m here is one of four ‘eco-lodges’, and the staff are attentive to my every need. I’m not surprised to learn that they’ve trained at Disney World in Florida through an exchange programme.

As evening falls on my first day, I settle onto the private deck of my lodge, watching the sun set over the water as boats from the nearby fishing communities appear. The fishermen set up small floating lanterns to attract tiny silver fish to their nets, creating a twinkling lightscape on the water’s surface. It’s hard to think of somewhere more perfect for a sundowner.

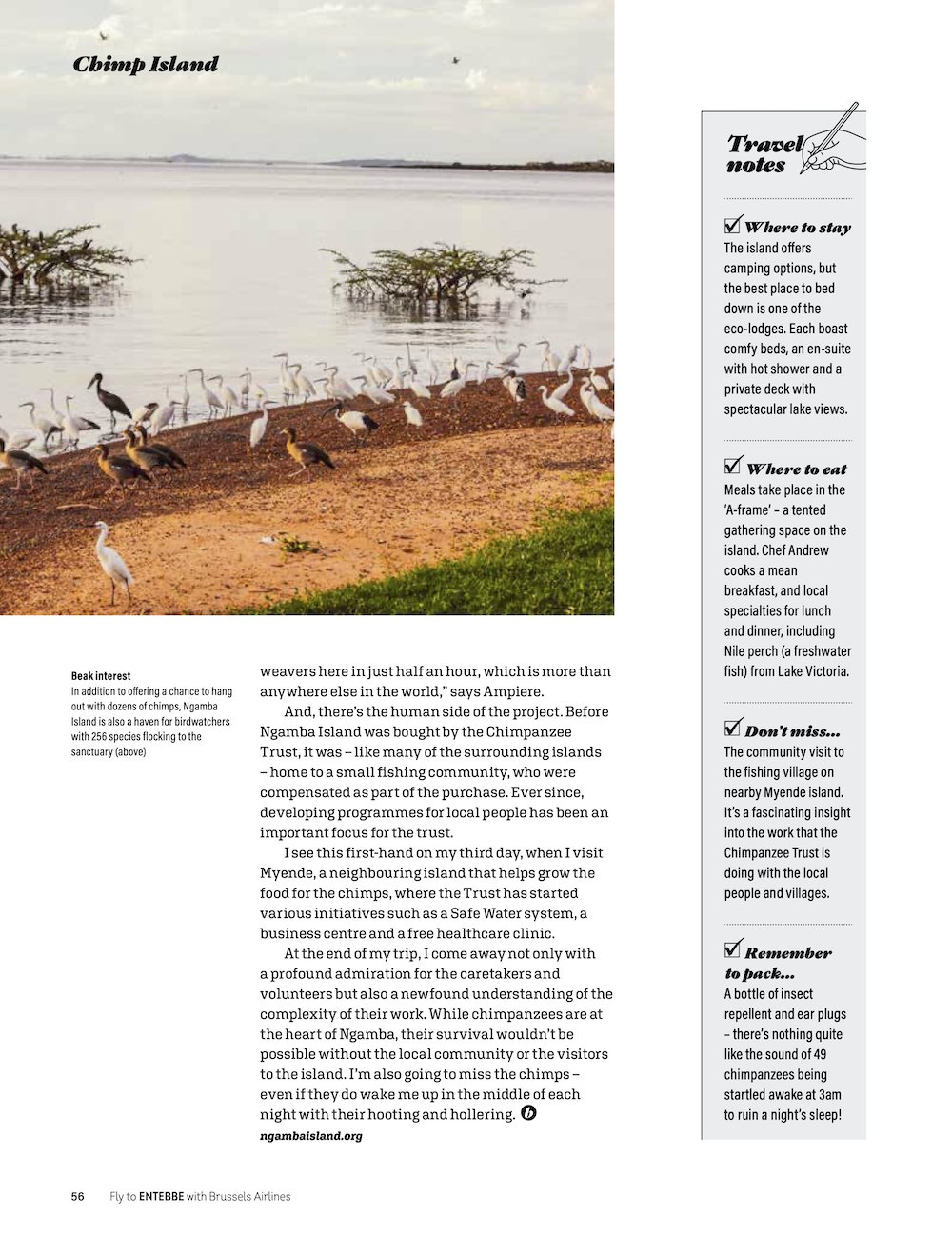

On my second day, I take a boat trip around the island and find that chimps aren’t the only attraction on Ngamba. Recently, birdwatching has become a popular activity on the island, which is home to 256 species of bird. “You can see four species of weavers here in just half an hour, which is more than anywhere else in the world,” says Ampiere.

And, there’s the human side of the project. Before Ngamba Island was bought by the Chimpanzee Trust, it was – like many of the surrounding islands – home to a small fishing community, who were compensated as part of the purchase. Ever since, developing programmes for local people has been an important focus for the trust.

I see this first-hand on my third day, when I visit Myende, a neighbouring island that helps grow the food for the chimps, where the Trust has started various initiatives such as a Safe Water system, a business centre and a free healthcare clinic.

At the end of my trip, I come away not only with a profound admiration for the caretakers and volunteers but also a newfound understanding of the complexity of their work. While chimpanzees are at the heart of Ngamba, their survival wouldn’t be possible without the local community or the visitors to the island. I’m also going to miss the chimps – even if they do wake me up in the middle of each night with their hooting and hollering. ngambaisland.org