N by Norwegian

Norwegian Air inflight magazine | October 2014

Trolls: Third Time’s a Charm

The Dam troll was an icon in the 1960s and 1990s, yet its Danish creator never fully reaped the rewards. Now a troll doll film by DreamWorks looks set to launch a third wave of troll mania – and right past wrongs.

It was perhaps the unlikeliest toy phenomenon of the 20th century – but the pot belly, ugly-cute face and colourful shock of hair made the troll doll an international phenomenon in the 1960s and again in the 1990s. The androgynous creatures were the subject of pieces in Time and Life magazines, met JFK in the White House, and generated an estimated US$3-5 billion (around NOK 32bn) in the 20th century.

Yet it’s often forgotten that the troll doll was created by a humble Danish woodcutter, Thomas Dam, and that his company Dam Things has received only a fraction of the mega-bucks garnered by troll dolls in the 50-odd years since their popularity exploded. After decades of legal wrangles, only in 2003 did the company finally wrest back the copyright of Dam’s original creation.

Now, though, things are looking up. In 2011, a deal was made with US animation giant DreamWorks, giving it the right to produce a film and television series about troll dolls, starting with a 2016 movie voiced by Jason Schwartzman and Chloë Grace Moretz. This was followed up by another deal the following year, in which DreamWorks bought the rights to the trolls outside Scandinavia (within Scandinavia, Dam Things continues to sell the trolls).

The DreamWorks deals are protected by strict confidentiality terms, but Dam Things’ CEO Calle Østergaard says it’s good news: “The deal is important to Dam Things as it will allow us to bring many more of Thomas’s works into the spotlight.” And, in a statement released at the time, he was quoted as saying he “could think of no better future for trolls, and for Dam Things.”

It all started in the 1950s in the small Danish town of Gjøl, when the long haired, arty woodcutter Dam couldn’t afford to buy a present for his daughter Lila. So he made a small carved timber doll with a shock of Icelandic sheep’s wool hair, modeled in his own image. Soon, Dam’s clients started noticing the doll with its wild woollen coiffure, and orders began to pour in.

“He had his own personal vision of trolls being something different from what people considered them to be from mythology – ugly, dangerous and bad luck,” says Østergaard, who joined Dam Things as CEO in 1997 when the company was “in great difficulties”.

“His trolls were meant to be kind and make people laugh. They are a little bit ugly but somehow still cute and cuddly. When I started working for the company, I was one of the very few people in Scandinavia never to have heard of the Dam troll – but you can’t help but love them, and I quickly

became hooked.”

In 1958, Dam began making the dolls commercially under his new Dam Things company name. The first dolls were made in the family living room from hay-stuffed latex and, the following year, in a small factory from more durable PVC – the plastic responsible for the distinctive sweet smell of the trolls.

Success for the troll came quickly, and before the first factory was completed, production had outgrown the space. A huge order was placed with Illum, the largest department store in Copenhagen, and soon tourists to the north were taking the unusual little dolls back to homes around the world.

In 1962, a pair of the trolls was gifted to Inge Dykins, a Danish woman living in Miami who was president of giftware firm Scandia House Enterprises. She was instantly hooked. As she told The Miami News in 1964: “People thought I was crazy to sell those ugly little things. I kept on trying, though, and introduced them at the International Toy Fair in New York City. The orders we received were beyond our wildest expectations.”

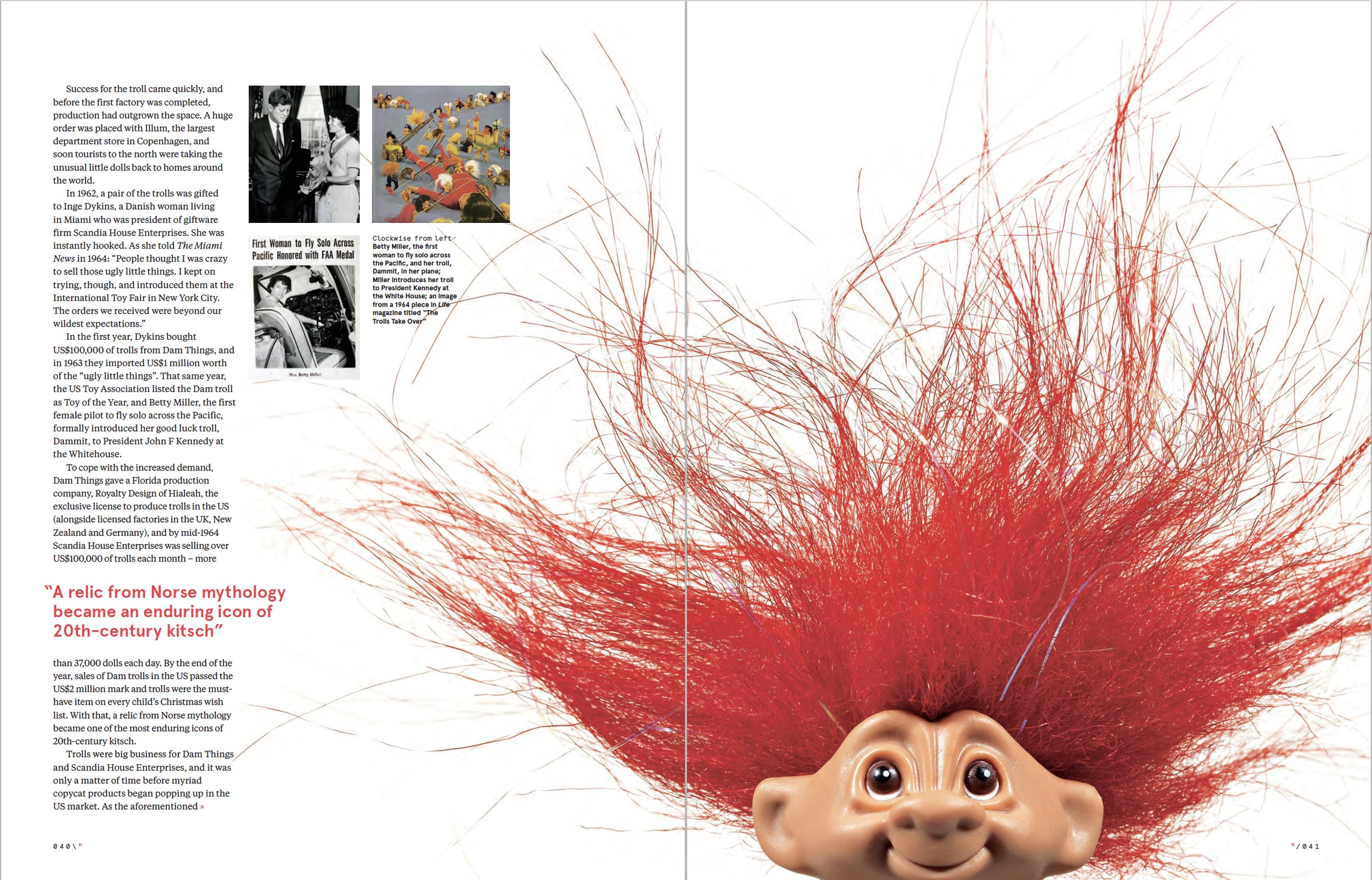

In the first year, Dykins bought US$100,000 of trolls from Dam Things, and in 1963 they imported US$1 million worth of the “ugly little things”. That same year, the US Toy Association listed the Dam troll as Toy of the Year, and Betty Miller, the first female pilot to fly solo across the Pacific, formally introduced her good luck troll, Dammit, to President John F Kennedy at the Whitehouse.

To cope with the increased demand, Dam Things gave a Florida production company, Royalty Design of Hialeah, the exclusive license to produce trolls in the US (alongside licensed factories in the UK, New Zealand and Germany), and by mid-1964 Scandia House Enterprises was selling over US$100,000 of trolls each month – more than 37,000 dolls each day. By the end of the year, sales of Dam trolls in the US passed the US$2 million mark and trolls were the must-have item on every child’s Christmas wish list. With that, a relic from Norse mythology became one of the most enduring icons of 20th-century kitsch.

Trolls were big business for Dam Things and Scandia House Enterprises, and it was only a matter of time before myriad copycat products began popping up in the US market. As the aforementioned newspaper article concludes: “With other firms taking a cue from her success and turning out their own trolls, Mrs Dykins also has hired legal counsel.”

This legal counsel, as it turned out, was to no avail. By 1964 the market was flooded with variations on Dam’s troll. Uneeda Doll Co sold what they called Wish-niks, Helen and Martti Kuuskoski of Finland created Fauni Trolls, and

Ace created Lucky Snooks – all of which shared the same distinctive bodies, faces and colourful shock of hair as Dam’s trolls. And – to the surprise of Dam – an error in the copyright notice of the original product meant that a 1965 court case ruled that the design of the troll was in the public domain in the US.

“Losing the copyright had a crippling impact on the business,” says Østergaard. “Thomas became very disillusioned and lost a lot of faith in his ability to manage a global brand, so he went back to Denmark to protect what was there. He was an artist, not a businessman.”

By the end of the ’60s, trolls and troll merchandise were everywhere – and, especially in the US and UK, almost all of it came from companies other than Dam Things. There were troll bed sheets, beanbags, hair accessories and jewellery, troll stationery, T-shirts, pencil-toppers, key rings and, of course, troll dolls – in every size, age and occupation imaginable.

Then, as all fads do, just as suddenly as they appeared, trolls disappeared – relegated to the back of closets and minds alike. As a journalist recalled in an article for Florida’s Evening Independent: “Wishniks were still available in some places in small quantities, but they just served as a depressing reminder of what trolls used to be. They might as well have broadcast on national TV that childhood was over.”

For the next 14 years, trolls all but vanished in the US and UK, resurfacing at garage sales and charity stores as a nostalgic reminder of a bygone era. In Denmark, however, Dam continued to craft his dolls for sale throughout Scandinavia and Europe, where stricter copyright laws prevented copies from entering the market.

“Popularity and sales varied during these years, but the troll never left Scandinavia,” says Østergaard. During this time, Dam developed 20 different expressions for the dolls – all of them happy or mischievous, with the familiar sparkling glass eyes – and, as Dam grew older, he introduced a grandma and grandpa troll. He was content, it seemed, to let the business continue to develop without the hassles (or wild success) he had encountered in the US.

That was until 1983, when a New York businessman named Steven Stark brought a Dam troll named George back from a work trip to Germany for his daughter. It was Stark’s wife, Eva, president of EFS Marketing Associates, however, who was most excited by George. “The Starks came knocking on Thomas’s door, keen to rebuild the troll brand in the US after it had been gone for many years,” says Østergaard. That same year, Eva began importing the trolls to the US from Dam Things, and reintroduced them at the Toy Fair in New York under the new name Norfin (a mash-up of the words elfin, orphan, Finland and Norway).

Just as the troll was making its comeback, Thomas Dam passed away in November 1989 at the age of 74. An article written shortly before Thomas’s death describes him as “very energetic and agile, with a wry sense of humour”.

Despite the enormous global success of his troll design, he thought of himself as a woodcarver until the end of his life – perhaps shying away from the idea of being a businessman because of the troubles he had encountered in the US during the 1960s. “He produced so many works that no one, even his family, has any idea of the number – there were literally hundreds,” says Østergaard.

The second invasion of trolls was as swift as the first, and in 1991 Dam trolls were, for the second time, named Toy of the Year by the US Toy Association – a distinction unique to the troll. The majority of Dam Things’ production was outsourced to factories in China, and a team of over 100 factory workers in Denmark produced the higher-end Good Luck trolls. As in the 1960s, however, Dam Things were plagued by copies of their troll, and only received a fraction of the sales from the top-selling toy, which by 1992 had reached US$700 million (across all brands). “Although Dam Things had a good few years in the 1990s, the rewards for the company should have been much bigger,” says Østergaard.

Everyone, it seemed, was jumping on the troll bandwagon – there were Original Battle Trolls from Hasbro, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle trolls, and even Barbie trolls. Ace, who sold Lucky Snook trolls in the ’60s, was back in the market with the popular Treasure Trolls, which sported colourful “wish stones” in their belly buttons, but one of the biggest companies to get into the troll business was US toy giant Russ Berrie. At the height of the troll craze, the company sold over 2,000 different troll-related products that brought in around US$300 million annually. So important were

trolls to the success of the business, that when Berrie married his third wife in 1993, he decorated the reception tables with 22cm-tall blue- and pink-haired trolls, and bride and groom trolls topped the wedding cake.

The market was saturated and in 1994 the inevitable collapse occurred and trolls again faded into obscurity. With a business focused entirely on the production of trolls – unlike their competitors who had other toys in their range – things didn’t look bright for Dam Things. “When I came to the company as CEO in 1997,” says Østergaard, “the company was in great difficulties.”

The first step was to regain the copyright, and in 2003 a Congressional law allowed the Dam family to restore copyright and become the sole manufacturer. With the copyright and a large settlement from Russ Berrie (protected by confidentiality clauses) in hand, Dam trolls began to interest various investors around the world. Dam Things, it seemed, was finally set to reap the rewards they deserved.

Unfortunately, however, success was limited. The company issued a license to American production company DiC Entertainment to create an ill-fated animated television series called Trollz (starring a group of five Best Friends For Life, or BFFL). The series was short-lived and the associated merchandise failed to create the hoped-for third wave of troll mania. So, in 2007, Dam Things found themselves back in the courtroom, this time filing a lawsuit against DiC Entertainment for misrepresenting its ability to market a modern troll doll toy campaign. In the end, the lawsuit was settled on undisclosed terms.

To all involved it was clear the company, now headed by Thomas’s son Niels, needed a new direction. “We decided we would shoot for the stars with a Hollywood production,” says Østergaard of the DreamWorks deal. Production started on the big-budget, musical comedy in 2012, with a story about how the trolls got their coloured hair by Emmy Award-winning writer, Eric Rivinoja.

With the copyright battles finally at an end, and an exclusive license in the hands of a US powerhouse, it seems that the anticipated third wave of troll mania will, rightfully, be all about the Dam troll. “Thomas always had a dream that his trolls would star in a movie, and if we had him here today, he would be so excited – it’s the fulfillment of his dreams,” says Østergaard. “I think it is safe to say that we are going to see the troll again in a manner that exceeds the past by magnitudes.” damworld.dk