N by Norwegian

Norwegian Air inflight magazine | October 2015

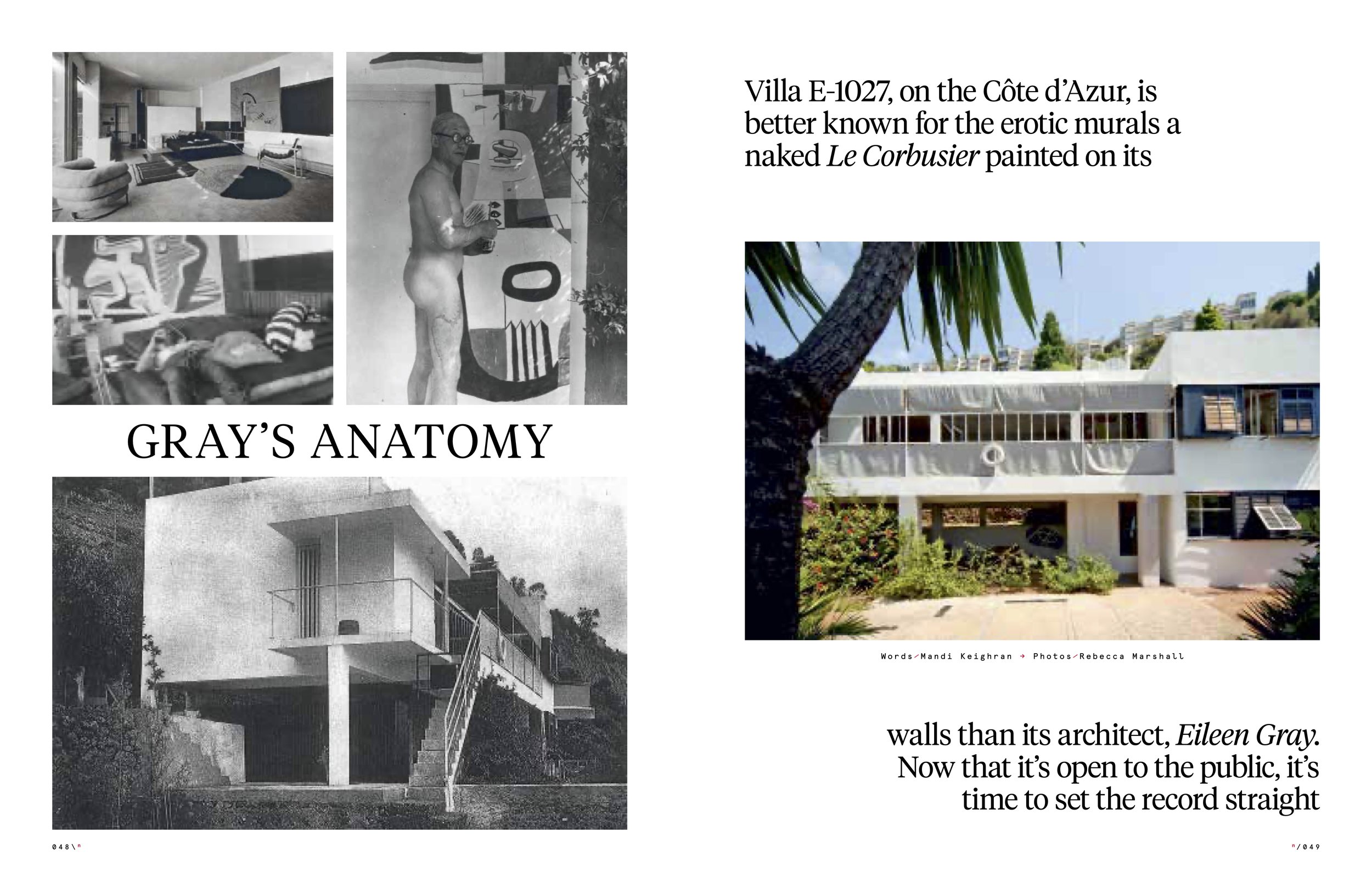

E-1027: Gray’s Anatomy

Villa E-1027, on the Côte d’Azur, is better known for the erotic murals a naked Le Corbusier painted on its walls than its architect, Eileen Gray. Now that it’s open to the public, it’s time to set the record straight.

A sticky sea breeze offers little relief from the unrelenting sun. Cicadas shriek in the heat, and tourists carrying vibrant beach umbrellas stare as they pass en route to one of the dozens of beaches dotted along this part of the Côte d’Azur. Surely they’re wondering why anyone would choose to sit sweating on this concrete footpath that runs alongside the railroad connecting Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, through Monaco, to Nice. Rebecca, a local photographer, tells me this is the hottest summer on record for the area. And, still, we wait. After 45 minutes, we realise our guides aren’t turning up. Villa E-1027 will remain tantalisingly out of sight behind a locked gate and a fence drenched in lush vegetation. There’s something poetic in this, given the reclusiveness of its architect, Modernist Eileen Gray.

The history of Gray’s E-1027 is a strange one. Beginning in the mid-1920s, it’s a story of love, betrayal, vandalism and murder, and – much to Gray’s annoyance during her lifetime – is inextricably entangled with Le Corbusier, the indomitable Swiss architect who pioneered Modernist architecture. It sounds like the overwrought plot of a Hollywood blockbuster, so it’s no surprise the story has recently been adapted for a film, The Price of Desire. Vincent Pérez stars as Le Corbusier, Orla Brady as Gray and Alanis Morissette as one of her lovers, Damia, a French singer and actress with a penchant for driving a convertible through the streets of Paris with her pet panther in the back seat.

Born in 1878 in the south-east of Ireland to an artist and a baroness, Gray was an accomplished designer whose work became emblematic of the Modern movement in the 1920s. Although renowned during her lifetime, she remained intensely private, and was once described by American journalist Thérèse Bonney as “unassuming, unexplosive, entirely consecrated”. Openly bisexual, Gray had ongoing intermittent relationships throughout the 1920s and ’30s with both Damia, and Romanian architect and editor Jean Badovici, who was 14 years her junior.

It was Badovici who encouraged Gray to pursue architecture, despite her never having trained. So, she decided to dedicate her inaugural architectural work to their relationship, and when she bought the land in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, which looks out over the blue expanse of Monte Carlo Bay, it was in her lover’s name. Work on the villa began in 1926, and for three years, Gray lived alone in a tiny flat, reputedly avoiding everyone but local builders.

Finished in 1929, the villa is an ode to sun and sea – floor-to-ceiling glass walls face the endless Mediterranean; terraces are shaded with sailcloth; in the garden, a sunken solarium lined with iridescent tiles offers a private place for nude sunbathing; and at the heart of the house a spiral skylight-staircase twists up toward the sun like the interior of a conch shell. With its concrete columns, open plan, and wide, horizontal windows, it was also a house conceived on the basis of Le Corbusier’s famous architectural manifesto, “Five Points of New Architecture”.

Befitting her private nature, Gray christened the retreat E-1027, the impersonal designation masking a coded reference to her relationship with Badovici that weaves their initials together – “E” for Eileen, 10 for the letter “J”, 2 for “B”, and 7 for “G”. She spent several summers at the villa, and in 1937 Le Corbusier visited for the first time with his wife, Yvonne, on Badovici’s invitation. He later wrote: “I am so happy to tell you how much those few days spent in your house have made me appreciate the rare spirit which dictates all the organisation inside and outside. A rare spirit which has given the modern furniture and installations such a dignified, charming, and witty shape.”

His visit the following year, however, did not go so well. Uninvited, he stripped naked and proceeded to paint the stark white walls with eight sexually charged murals. His reasons behind the act have been lost to history, but according to popular lore, he took issue with a woman creating such a shining example of an architectural style he considered his own, and was determined to place his own mark on the villa. An outraged Gray called it “an act of vandalism”, and soon left both the house and Badovici, with whom her relationship had grown strained. She built herself a new home in the nearby village of Castellar, and although she and Badovici remained friends, she never returned to E-1027.

Since then, the story of the villa has been a chequered one. During the war, it was occupied by Italian and then German soldiers, who used the walls for target practice; and in 1950, Le Corbusier further intruded, buying the neighbouring land and erecting a hut he called Le Cabanon for himself and his wife, and a two-storey hostel. When Badovici passed away in 1956, the property passed to his sister who lived in Romania and was forbidden to own overseas property. Later that year, at a Paris exhibition, the design of the villa was misattributed to the better-known Badovici, a falsehood that was perpetuated by Le Corbusier, who wanted to preserve his murals. To this end, he arranged for Marie-Louise Schelbert, a wealthy Swiss widow, to purchase the declining house.

Schlebert maintained the villa, but in 1980 it was taken over under shady circumstances by Peter Kägi, a gynaecologist and morphine addict who was accused by Schelbert’s children of having had a hand in the widow’s death. In 1996, Kägi himself was found murdered in the living room (two vagrants he had invited into the house were later arrested and imprisoned). Throughout the noughties, E-1027 was abandoned to squatters, who sprayed the walls with graffiti, and so it remained, mostly forgotten and going to ruin.

Meanwhile, Gray’s furniture design was undergoing a revival, driven by London-based furniture retailer and designer Zeev Aram, who began to collaborate with the designer in 1973 to introduce her furniture to a global audience. In 2009, an original Dragons armchair by Gray, which had been owned by Yves Saint Laurent, sold at Christie’s in Paris for £19m (around NOK240m), making it the world’s most expensive piece of 20th-century furniture design.

The villa was purchased by the Conservatoire du littoral (the French government agency responsible for protecting the coastline) and restoration took place between 2006 and 2010 – funded by an alliance between British businessman Michael Likierman, Robert Rebutato (the son of the owner of L’Étoile de Mer, a café on the site that Le Corbusier frequented), the French government, and New York non-profit Friends of E-1027. In 2014, an organisation called Cap Moderne was formed to run the site. The villa finally opened to the public by appointment in July this year, and there is a €5m (NOK46m) plan for the site, including the conversion of a railway wagon by the station into a library, ticket office and shop.

With E-1027 off the agenda for us, Rebecca and I turn our attention from Gray to Le Corbusier. We take a short walk down the concrete path – named Promenade Le Corbusier – to the rocks from which the architect would take his daily swim when staying at Le Cabanon during last few years of his life. “How nice it would be to die swimming towards the sun,” he reputedly once remarked to a colleague, and it’s here that in 1965, at the age of 77 and against his doctor’s orders, Le Corbusier went for an inauspicious final swim, during which he suffered a fatal heart attack.

Having seen the spot of his death, we decide to make the short trip to the Cimetière de Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, where he was laid to rest beside his wife. He designed the grave for himself and Yvonne after her death eight years earlier. Adding a slightly macabre – or romantic – element to the story are rumours that the architect kept one of Yvonne’s vertebra as a token after she was cremated, carrying it with him in his pocket for the rest of his life. “Do you know the way to Le Corbusier’s grave?” I ask the waiter at Le Cabanon beachside restaurant, named for its proximity to the architectural site.

“The Swiss architect?” he asks in return. “He’s buried in Switzerland.” We insist he’s buried right here, in the local cemetery. “You need to ask someone old where the cemetery is,” he tells us. “Why would I know where the Swiss architect is buried?”

Thankfully, our taxi driver, Rogi, knows exactly where the Swiss architect is buried. He is, however, decidedly nonplussed by the gravesite or the architect.

“Why do you want to go see Le Corbusier’s grave?” he asks. “I saw it once, when an Indian family from Chandigarh (the city in northern India for which Le Corbusier created the master plan) came to pay their respects. The man brought his entire family – grandparents and grandchildren. I drove them up here, and that’s when I saw it. It’s not so special. You should just make up a story and go to the beach!”

Despite Rogi’s advice, we continue the short drive up a winding mountain road to the cemetery. We soon arrive at what must be one of the world’s most spectacular final resting places. Positioned at the edge of the medieval hillside town, it gazes out over an azure ocean dotted with yachts. From up here, even the super yachts moored off Monaco’s coast look quaint and picturesque. We wander through row upon row of graves, in search of the architect and his wife, and soon find them, to our left, on the third tier down. “Is that it?” asks Rebecca, and we can’t help but laugh.

It’s an astonishingly modest grave for a man reputed to have been in possession of such an ego. A simple bed of brutally stark concrete – of course – marked by a triangular block, inlaid with a hand-painted ceramic plaque, and a rotund planter housing a wilting succulent. Weeds sprout through cracks in the concrete, and a small offering of an architectural model sits at one corner, weighed down by pebbles – presumably left by one of the assorted architects and students who make the pilgrimage to Roquebrune-Cap-Martin from around the world.

Although Gray and her villa have remained elusive for us today, the hope is that visitors will soon make the pilgrimage to Roquebrune-Cap-Martin not only for Le Corbusier. On my return to London, I email the organisers of Cap Moderne, explaining how disappointed I was that I didn’t get to visit Gray’s villa. “It is a very sad story,” came the simple reply. I can’t help but think that it’s an apt description of Gray’s relationship to her villa. Hopefully, however, following its restoration and the ensuing publicity, this story will have a happy ending.