N by Norwegian

Norwegian Air inflight magazine | March 2016

Taxi Driver

New York’s iconic yellow cabs have been a part of the city for over a century, but who’s behind the wheel?

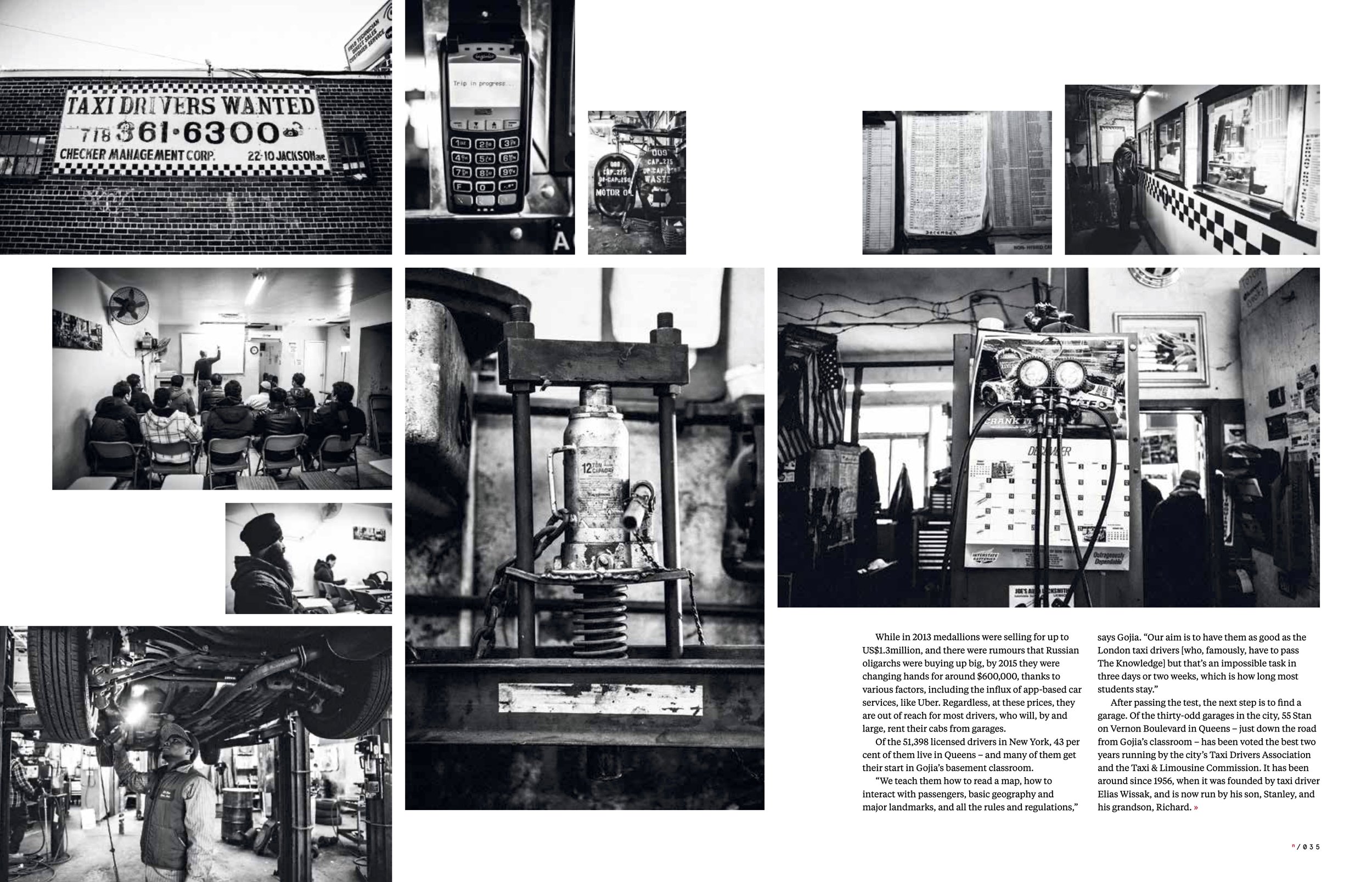

In a windowless basement beneath a Tibetan restaurant in the part of Jackson Heights, Queens, known as Little India, 10 grown men sit in rows behind tiny school desks. Outside, the L train thunders past, momentarily drowning out the endless stream of traffic noise.

“Cell phones off, paper and pencils ready,” says teacher AJ Gojia. Today’s lesson is on Central Park. “Central Park has how many sides? Four! What is the name of the north side? CPN! What does that stand for? Central Park North!” His students diligently repeat his answers and take notes. They have, after all, each paid US$600 to attend Gojia’s class, which aims to teach them the basics needed to pass the licensing test to become a taxi driver for the city’s iconic yellow cabs.

Hacks – a term for New York’s cabbies that originates from the horse-drawn hackney carriages that preceded motorised cabs – have a long history in New York. Today, the city is home to yellow cabs, green cabs – known as “boro taxis” – that were controversially introduced in 2013 to pick up from the outer boroughs, and over 40,000 other for-hire vehicles, including around 14,000 Uber cars.

But, it’s the yellow taxis that remain an emblem of the city. Every year, they transport 236 million passengers on an estimated 175 million rides across New York. Used to ferry New Yorkers and out-oftowners alike, they can be found criss-crossing the five boroughs at any time of day or night. They also offer many visitors their first glimpse of New York, as they make their way from the airport.

Even for a first-timer, New York cabs are familiar, recognisable from the countless films and television shows that use them to set the scene. From the opening of Breakfast at Tiffany’s to Robert De Niro’s portrayal of lonely, disillusioned Travis Bickle in Scorsese’s 1976 classic Taxi Driver and Danny DeVito’s despotic dispatcher, Louie De Palma, in American sitcom Taxi. And yet, most of those who recline on the upholstery don’t really know much about where they came from, and the lives of those who drive them.

The first yellow cabs appeared in 1912, when businessman Albert Rockwell started his Yellow Taxicab Co (apparently, yellow was his wife Nettie’s favourite colour). By the 1930s, however, the Great Depression had hit, and there were more cab drivers – an estimated 30,000 – than passengers. So, in 1937, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia introduced the medallion system, which limited the number of licensed taxis to 11,787. Incredibly, this number remained stable until 1996, when the Taxi & Limousine Commission (TLC) added 133 new licenses. Today, there are 13,605 medallion cabs in the city.

While in 2013 medallions were selling for up to US$1.3million, and there were rumours that Russian oligarchs were buying up big, by 2015 they were changing hands for around $600,000, thanks to various factors, including the influx of app-based car services, like Uber. Regardless, at these prices, they are out of reach for most drivers, who will, by and large, rent their cabs from garages.

Of the 51,398 licensed drivers in New York, 43 per cent of them live in Queens – and many of them get their start in Gojia’s basement classroom. “We teach them how to read a map, how to interact with passengers, basic geography and major landmarks, and all the rules and regulations,” says Gojia. “Our aim is to have them as good as the London taxi drivers [who, famously, have to pass The Knowledge] but that’s an impossible task in three days or two weeks, which is how long most students stay.”

After passing the test, the next step is to find a garage. Of the thirty-odd garages in the city, 55 Stan on Vernon Boulevard in Queens – just down the road from Gojia’s classroom – has been voted the best two years running by the city’s Taxi Drivers Association and the Taxi & Limousine Commission. It has been around since 1956, when it was founded by taxi driver Elias Wissak, and is now run by his son, Stanley, and his grandson, Richard.

“The 55 Stan garage is symbolic of New York City,” says Richard. “It’s a melting pot with 600 drivers from all over the world – African, Haitian, Middle Eastern – and we all get along here… The drivers we used to call ‘cowboys’ and ‘outlaws’ that drove in the middle of the night, ripping customers off, have mostly been weeded out by the new TLC regulations. The fellows that are in it for a real job and want to stay with it, they hold onto their licences – it’s how they support themselves and their families.”

Cabbies drive an average of 290km per shift, and a taxi typically travels 113,000km every year – which is enough to travel around the world nearly three times. And, every mile is a hustle to make a buck. “It’s every man for himself out on the streets,” says Graham Hodges, author of Taxi! A Social History of the New York City Cabdriver, who drove a cab for five years to put himself through school before leaving in 1975 to pursue an academic career. “It is a tiring job.”

It’s also a risky job. According to a BBC World Service radio documentary, Yellow Cab Blues, which aired in 2014, taxi drivers are 30 times more likely to be killed on the job than the average worker, and 80 times more likely to be robbed.

There’s also the financial uncertainty. Although drivers average a net hourly rate of between $14 and $31, most rent their cabs from garages for 12-hour shifts, at a cost of around $120, meaning they start every shift at a loss. Add in gas costs, and driving a taxi is one of the few jobs in the world where you can finish a nine- to 12-hour shift and have less money than when you started.

So, what does it take to survive – and succeed – as a hack in the Big Apple? According to both Gojia and Richard Wissak, it’s simple: the ability to engage with your passengers. “You gotta have personality,” says Gojia. “If you’re talkative and have conversations with people, you’ll make a good living. A lot of people treat cab drivers like therapists – tell them stuff they would never tell anyone else because they know they won’t see them again. It’s like free therapy, and people will tip well for that.”

“You also have to have patience, and know when to keep your mouth shut,” adds Wissak.

The biggest challenge to the industry in recent years, however, is the rise of app-based car services, such as Uber. Total yellow-cab rides were down 10 per cent in the first half of 2015, compared to the same period in 2014, while there were 100,000 Uber trips in a single month – a fourfold increase from the same time the year before.

But, it’s not all bad. The Uber revolution has also meant increased options for drivers, and less competition for yellow cabs. This might make things harder for fleet owners, who need to keep their cars out on the road, but according to some of the drivers, it’s generally improved conditions for those who have chosen to stick with yellow cabs.

“Before there were more drivers than cabs,” says Gojia. “You had to tip the dispatcher $30 if you wanted a cab – bribe your way in – and they acted like they were doing you a favour by giving you a taxi. Now, there are fewer drivers. The garages have free donuts and coffee, you take a seat and get a cab in five minutes.”

So, what does the future hold for New York’s yellow cabs? “I could be very grim about it and say that Uber is going to take over,” says Hodges. “That could very well be the case, but I personally think that people will realise why the yellow cabs are so regulated, and see the benefit in that.”

Wissak agrees. “This city is full of impulsive people who want to be able to raise their hand on the spur of the moment and have a car stop. So, I think yellow taxis are going to stick around,” he says. “You have to be a character to drive New York City, though – that’s what we say to the newcomers. And that they’ll always be able to tell their grandchildren they drove a yellow cab in New York City.”

RICHARD WISSAK

The fleet owner

New York’s number one taxi company – 55 Stan –was started the old fashioned way, says Richard Wissak, the garage’s third-generation owner operator. Wissak’s grandfather, Elias, bought his first medallion in 1938, and established the garage in 1956.

“My family didn’t come over on the Mayflower, so they did whatever they could to earn a living in those days,” says Richard. “My grandfather liked the business, and slowly accumulated more cabs, then passed the taxi garage down to my father, Stanley.” Now 87 years old, Richard’s father still comes into the garage in Long Island City, Queens, by 4am most days to work as a dispatcher.

Richard worked part-time at the garage in high school, before heading to Boston to study law. But, after a number of years as an attorney, he decided it was about time for him to return to the family business.

“In a city like New York that never sleeps, anything can happen – accidents, sick passengers, cars breaking down, lost property, complaints. This is a 24-hour, seven day a week operation, and I’m here six days a week, rain, snow, or heat. I always liked this business, though.”

The garage is home to 140 cabs and has from 500 to 600 drivers on the books. For several decades, this included Johnnie “Spider” Footman – who, at 94, was New York’s oldest cabbie when he passed away in 2013. Stanley and Richard know all of them. “The drivers are our customers,” says Richard. “Just like the passengers in the back seat of the taxi are the drivers’ customers.”

ERNEST

The taxi driver

Ernest emigrated to New York from Greece 50 years ago, and has been driving cabs for a living since 1978. “Nobody really likes their job,” he says. “But this job gives you independence and you get used to it. I tell you, most of the passengers are nuts, but you can work out your differences with them. Friday and Saturday nights, they’re out of control, but it’s okay.”

He’s been working out of the 55 Stan garage for the past decade. “These guys are on our side. We have an excellent office here. The TLC suspended my licence and couldn’t tell me why. I talked to these guys and – boom, boom – it took me just a few hours to get back to work.” The main challenge of being a cab driver? “The TLC,” says Ernest. “It’s very chaotic, and the rules and regulations can be brutal.”

GRAHAM HODGES

The taxi historian

Academic Graham Hodges got his hack licence back in 1971, when he was a student at the City College of New York. “It was easy to get a licence then,” he says. “I went to a garage on Friday, and by Monday I had my licence – they even paid for it. On my first shift, I wound up with US$70 in my pocket, which was more money than I’d ever earned.”

After five years, though, he called it quits. “The long hours and sitting in a car seat with bad springs was very difficult for me physically, and out on the street it’s very competitive – every man for himself. It was long enough to get to know the job, though, and an important experience for me.”

Several years later, he was looking for a dissertation topic as part of his PhD in colonial history at New York University when he realised he felt an affinity with the city’s 19th century cartmen, drivers of the two-wheeled carts that preceded taxis. In 1986, the dissertation became Hodges’ first book, but he couldn’t shake the feeling there was more of a story to tell. “I kept dreaming about modern-day cab drivers. I always knew it could be a book.”

Twenty years later, he got a publishing deal, and wrote Taxi! A Social History of the New York City Cabdriver – and his reputation as a taxi historian was cemented. These days, he works as a professor of history at New York’s Colgate University and is regularly quoted in the media as an authority on the city’s cabs – a role he’s proud to play. “Taxi drivers are one of the most powerful images of New York City,” he says. “Right up there with the Empire State Building.”

LINCOLN STEVENS

The mechanic foreman

Lincoln Stevens has been working as 55 Stan’s mechanic foreman for the past decade, heading up a team of 15 mechanics who keep the garage’s 140 cars in top shape. “We have a schedule. Every car has to come into the shop twice a month – we have to keep them sharp.”

The garage runs a full hybrid fleet of late-model Fords. Using hybrids means a driver will get through a maximum of four gallons of gas, rather than 15, which makes them cheaper to maintain. Cars are kept in use for two years before being sold. “We check everything, but always the lights, tyres and passenger area – passengers cause a lot of damage.”

Stevens’ team pays particular attention to cars heading into their three annual TLC inspections. “We have a 98.8 per cent pass rate, because we don’t wait for cars to break down or for the TLC to tell us what’s wrong. It’s not standard practice for most fleets, but we’re different. We know the rules and how to keep them.”

AJ GOJIA

The taxi tutor

AJ Gojia began driving cabs in the early ’90s to work his way through college. “Taxi driving was good money,” he says. “My college buddies were working in retail, making minimum wage. I put in half the time and made twice the money. Plus, it was flexible when I had finals.”

One day, he came across a job ad for a taxi instructor in a Pakistani newspaper. “I fit the bill, but I was only 21. Most of the students were in their forties, so they said I was too young. Two weeks later – boom – they called me back. I had two days’ training before I taught my first class.”

He taught night and weekend classes, in addition to his already hectic schedule of driving 12-hour shifts, four nights a week, and college. “Sleeping is not on the top of my list in life,” he says. “I get four hours and I’m a happy camper.”

Ten years later, he decided to open his own taxi-tutoring school in Queens. He runs four daily sessions, teaching up to 30 students how to read maps, find landmarks, and interact with customers.

“Driving is a great way to make a living. Teaching is the same – you meet new people every day. I get asked if it’s monotonous to teach the same material every day, but it’s a challenge to have someone who has never gone to a formal school and someone with a master’s degree in the same class and make sure they both pass.”

Last year, a television production company approached Gojia about a reality programme set at the taxi school. “I told them I wasn’t interested in making a dime off of my students’ personal lives. My business does well, and I can sleep at night knowing I help people. I sleep fantastically… for four hours. I don’t need more sleep. You sleep when you die, it’s fine.”