Icon

Autumn 2023

Max Lamb

As he continues his ongoing exploration of the surprising possibilities of everyday materials, designer Max Lamb is about to launch a new body of work that offers a new life after delivery for the cardboard box.

The humble cardboard box is ever-present in our lives – it protects our online shopping, conveys our possessions when we move house, and can be used to store or transport almost any product. As far as packaging materials go, it’s also incredibly sustainable, thanks to its ability to be endlessly recycled. Yet, in all of these applications, the cardboard box is a supporting actor. British designer Max Lamb is challenging this perception by transforming cardboard into the star of a new collection of furniture.

“I value every raw material, and this idea has been bubbling away subconsciously ever since I’ve been a practising designer,” says Lamb. “I’ve been keeping hold of cardboard boxes with a view to transforming them into more permanent, functional pieces with a primary, rather than secondary, function.”

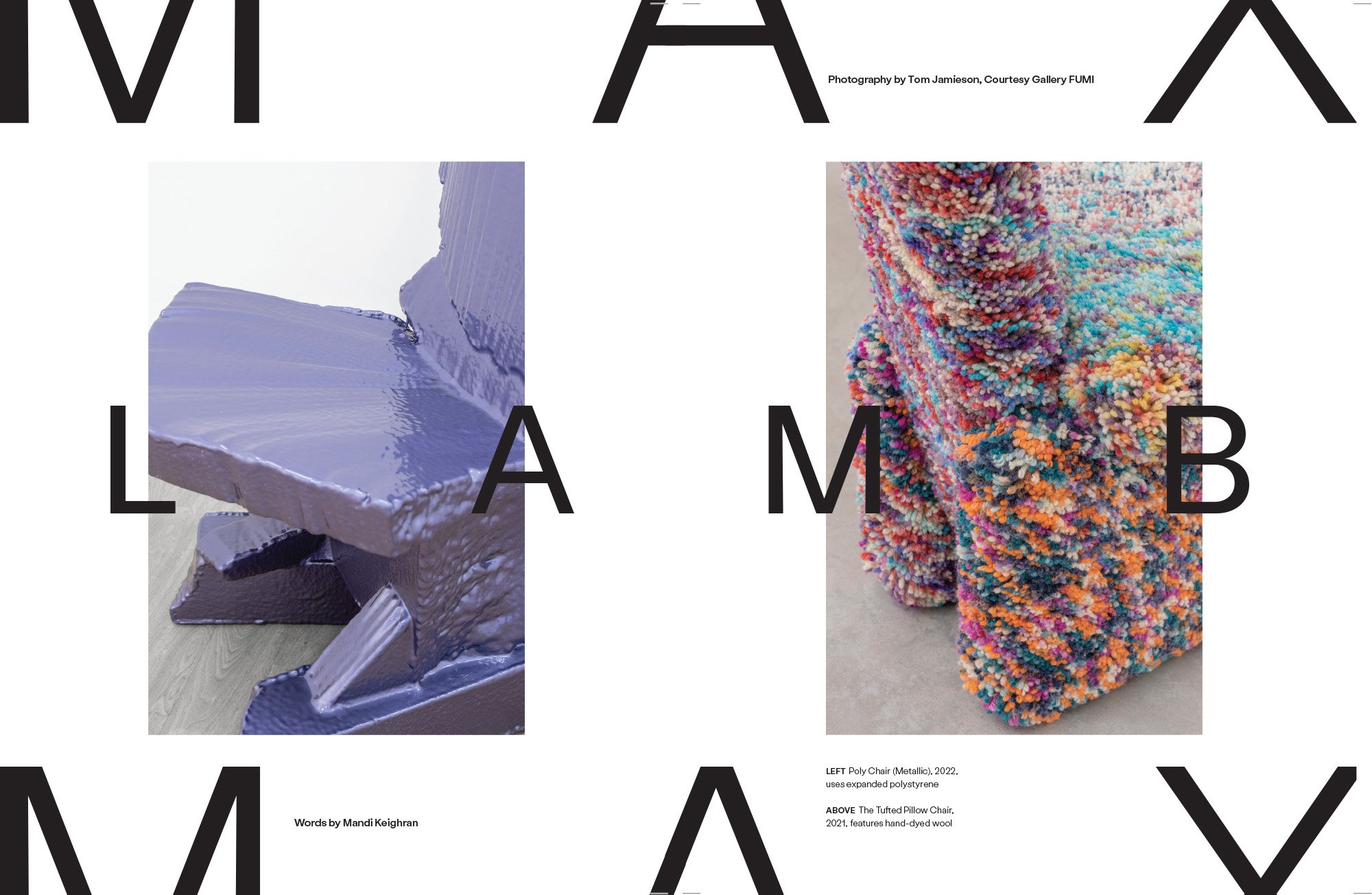

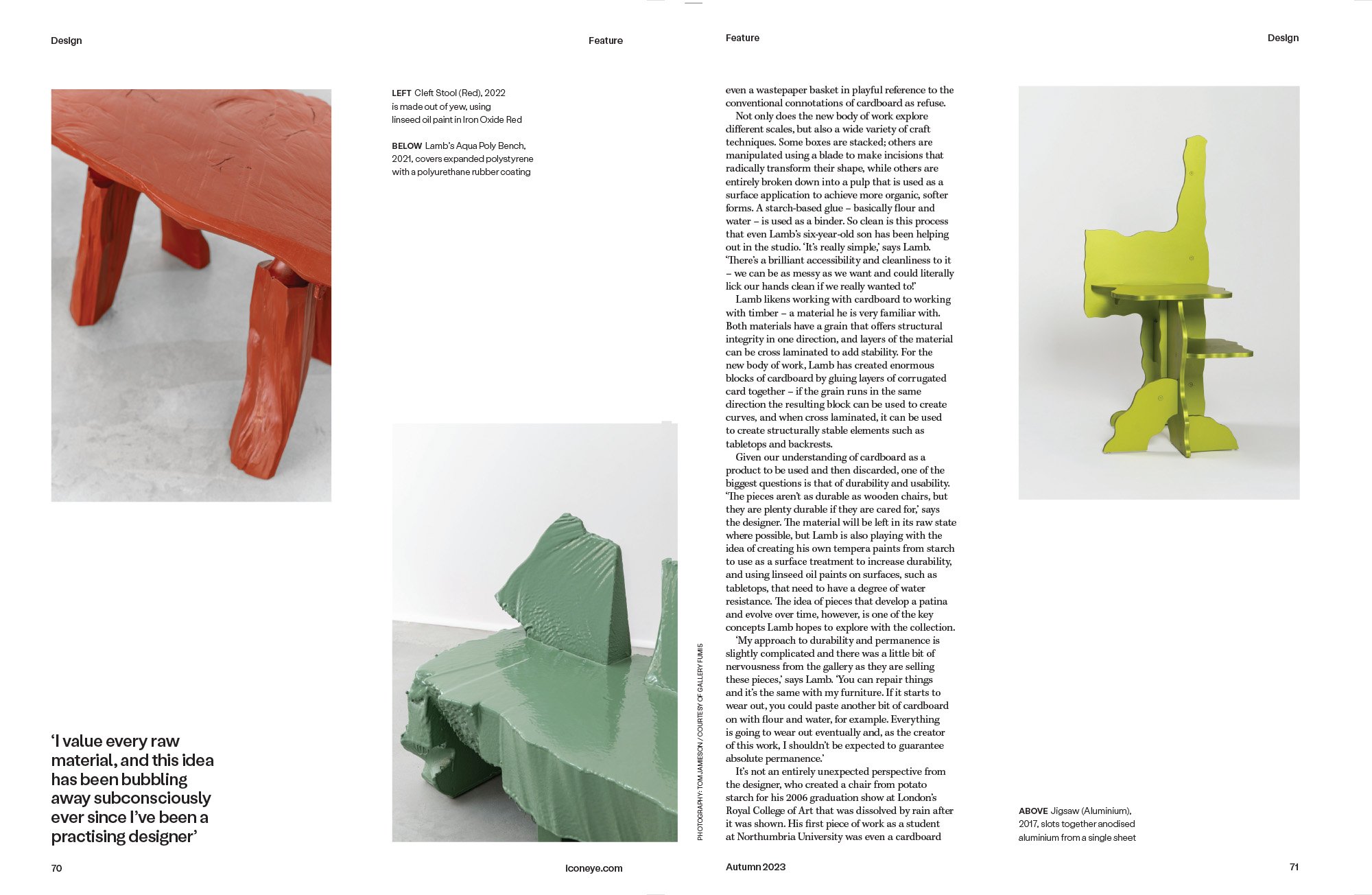

In his practice, the London-based designer explores the boundaries between art and design, bringing a sustainable and considered approach to his work. Never afraid to experiment with styles or design processes, Lamb has worked with everything from the hand-dyed wool of his Tufted Series to the anodised aluminium of the Jigsaw Series, always finding ways to give scrap material new life.

His latest collection, Boxes, which will be shown at Gallery FUMI in London from 5 October to 18 November, is a continuation of this ethos. The title reflects the simplicity and pragmatism of the material itself, as well as Lamb’s knack for material experimentation.

There are more than 30 pieces in the collection, exploring different scales – from small stools and bowls to armchairs and coffee tables. The largest piece is a “monster” dining table, an assemblage of cardboard boxes, while a wastepaper basket playfully references the conventional connotations of cardboard as refuse.

Not only does the new body of work explore different scales, but it also incorporates a wide variety of craft techniques. Some boxes are stacked; others are manipulated using a blade to make incisions that radically transform their shape, while others are entirely broken down into a pulp that is then applied as a surface treatment to achieve softer, more organic forms. A starch-based glue – essentially just flour and water – is used as a binder. The process is so clean and accessible that even Lamb’s six-year-old son has been helping out in the studio. “It’s really simple,” says Lamb. “There’s a brilliant accessibility and cleanliness to it – we can be as messy as we want and could literally lick our hands clean if we really wanted to!”

Lamb likens working with cardboard to working with timber – a material he is very familiar with. Both materials have a grain that offers structural integrity in one direction, and layers can be cross-laminated to add stability. For Boxes, Lamb has created enormous blocks of cardboard by gluing layers of corrugated card together – when the grain runs in the same direction, the resulting block can be used to create curves, while cross-laminating provides structural stability for elements like tabletops and backrests.

Given our understanding of cardboard as a disposable material, questions of durability and usability naturally arise. “The pieces aren’t as durable as wooden chairs, but they are plenty durable if they are cared for,” Lamb explains. The material will be left in its raw state where possible, but he is also exploring ways to enhance its longevity, including making his own tempera paints from starch and using linseed oil paints on surfaces that require some water resistance. The idea of allowing pieces to develop a patina and evolve over time is central to the collection.

“My approach to durability and permanence is slightly complicated, and there was a little bit of nervousness from the gallery as they are selling these pieces,” Lamb admits. “But you can repair things. If a piece starts to wear out, you could paste another bit of cardboard on with flour and water, for example. Everything is going to wear out eventually, and as the creator of this work, I shouldn’t be expected to guarantee absolute permanence.”

It’s not an entirely unexpected perspective from a designer who once created a chair from potato starch for his 2006 graduation show at the Royal College of Art – only for it to dissolve in the rain after being exhibited. His first piece of work as a student at Northumbria University was even a cardboard coffee table that his parents still use 23 years later.

“These pieces are incredibly strong and durable – I’m excited to demonstrate how strong paper can be,” says Lamb. “Everybody has cardboard in their house, and we just throw it away on a daily basis. There’s something super beautiful about this accessibility. I’m trying to put the emphasis on the cardboard and make it the protagonist.”

While Boxes radically challenges our perception of cardboard’s potential, the value of craft, and the permanence of the objects we use, Lamb isn’t the first designer to experiment with the material. Frank Gehry’s cardboard furniture is perhaps the most famous precedent, and Lamb was well aware of its cultural impact while developing his own collection—particularly the way Gehry’s designs have become iconic despite being crafted from a material traditionally seen as ephemeral.

“The Beaver Chair is almost designed with the knowledge that it’s going to disintegrate and, through use, become soft,” says Lamb. “I’m taking a slightly more rigid approach to crafting, making things very structural and archetypal in their form—I’m having to really engineer the cardboard to give it structural integrity.”