N by Norwegian

Norwegian Air inflight magazine | November 2016

New York is a real chess city…

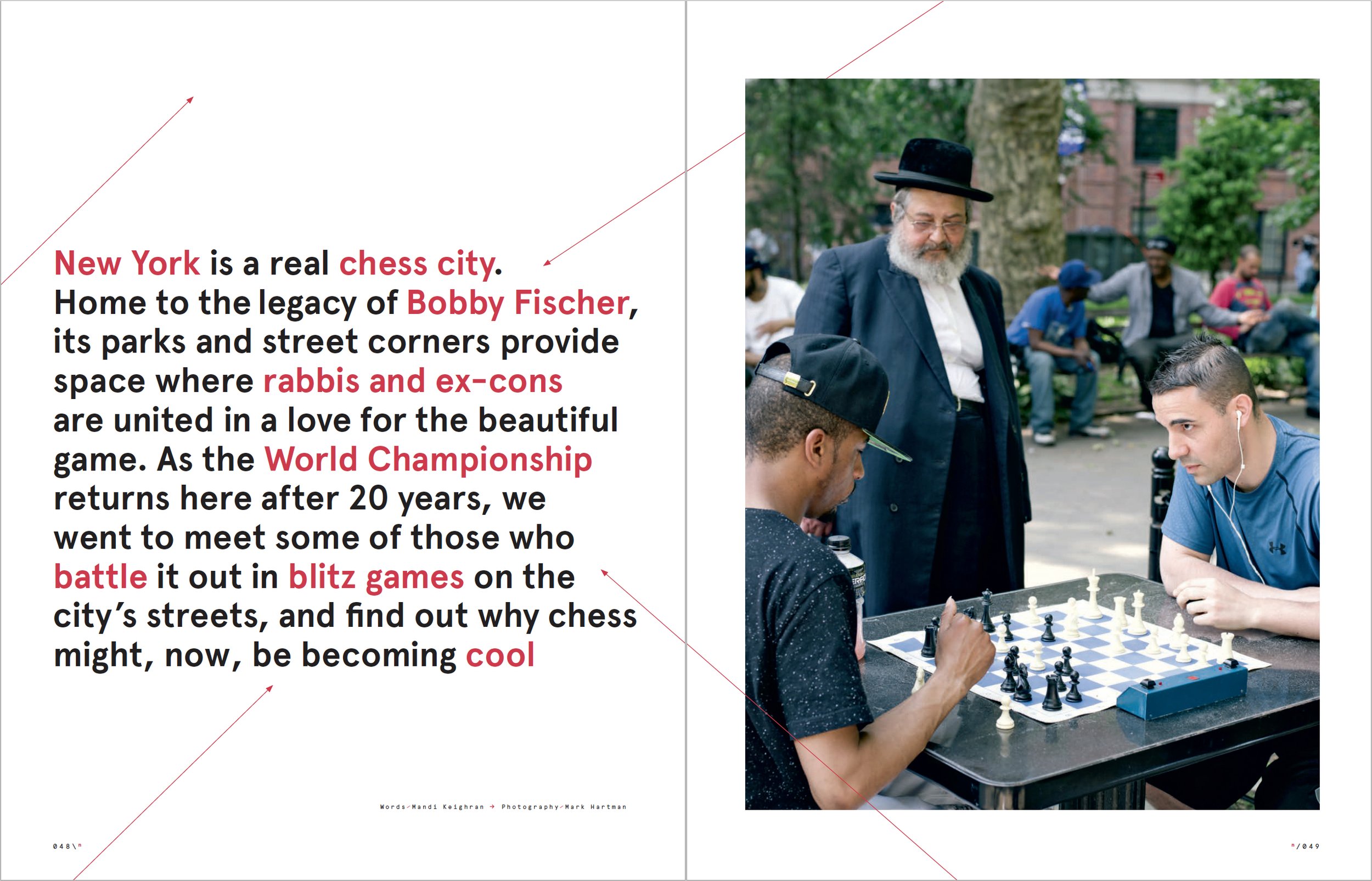

New York is a real chess city. Home to the legacy of Bobby Fischer, its parks and street corners provide space where rabbis and ex-cons are united in a love for the beautiful game. As the World Championship returns here after 20 years, We went to meet some of those who battle it out in blitz games on the city’s streets, and find out why chess might, now, be becoming cool.

Exit the subway at Union Square in Lower Manhattan, and you’ll find a messy assemblage of chess players. There’s an old man in bedraggled flannel silently playing a twenty-something guy in baseball cap who’s listening to music through headphones; a middle-aged woman in a leopard-print bodice and oversize sunglasses with a board cluttered with lucky charms; and a beefy guy chain-smoking cigarettes facing a businessman on his lunchbreak.

Some are just passing through, while others look settled in for the day, with adjustable office chairs, pillows and snacks. Balancing their boards atop stacked milk crates, cardboard boxes and makeshift card tables, this motley crew calls out to passers-by – competing for attention against the chanting of a group of orange-robed Hare Krishna – cajoling them into US$5 (NOK40) games on the clock.

There’s nowhere in the world where chess is played the way it is in New York. The scene is as diverse as the city itself, from the venues and customs to the myriad characters who play it.

Of course, there are the official clubs and tournaments that you find everywhere; there’s even the “chess district” – an area of Manhattan along Thompson Street between West 3rd Street and Bleecker Street, which has been populated by numerous chess shops, like Chess Forum and the famous Marshall Chess Club, since the game’s heyday in the 1960s and ’70s when controversial American Grandmaster and former world champion Bobby Fischer brought chess into mainstream popularity.

Much of the real action, though, takes place in parks and on street corners – the main ones being Union Square, Washington Square Park and Central Park’s purpose-built pavilion, Chess & Checkers House. Here, blitz chess – a variation of fast chess in which players have 10 minutes or less on the clock – is the game of choice. While the 64 black-and-white squares, and the collection of plastic pieces will be familiar to most, the atmosphere is anything but. Trash talk and sleight of hand are as much a part of the game as openings and strategy; the clock as important a piece as the queen.

“Most of the guys who play in the parks are hustlers,” says Michael Propper, co-founder with Russ Makofsky of Chess NYC, a local organisation headquartered in a Greenwich Village basement jazz bar that promotes the game, and offers lessons and tournaments. “A lot of them learn how to play in jail, where you either lift weights or play chess. They’re better than the average chess player and they know how to cheat really well. They think they’re beating the world with their $5 games. Then there’s a few outstanding guys – Russian Paul [who had a cameo in hit 1993 film Searching for Bobby Fischer] is one of them. He works for us now as a tutor.”

Visiting the parks on a sunny afternoon in July, the most noticeable thing is the unexpected aggression of the game, which goes against any notion of chess as a nerdy pastime for socially awkward kids and genteel elderly men. Pieces are grabbed off the table and smacked down with astonishing speed. It is both a social activity and deadly serious.

“Chess in New York’s parks is not like it is in Europe,” says John, who works at Chess Forum, which bills itself as New York’s last great chess store and sells everything from traditional Staunton sets to Star Trek and limited-edition neon-lit glass sets, as well as offering games by the hour in a parlour out back. “There are the same types of characters – weird old men yelling at each other – but here it’s almost exclusively for money. God bless, I have no problems with hustling, but it’s a different scene. From a theoretical perspective, it’s also a different way of playing chess.”

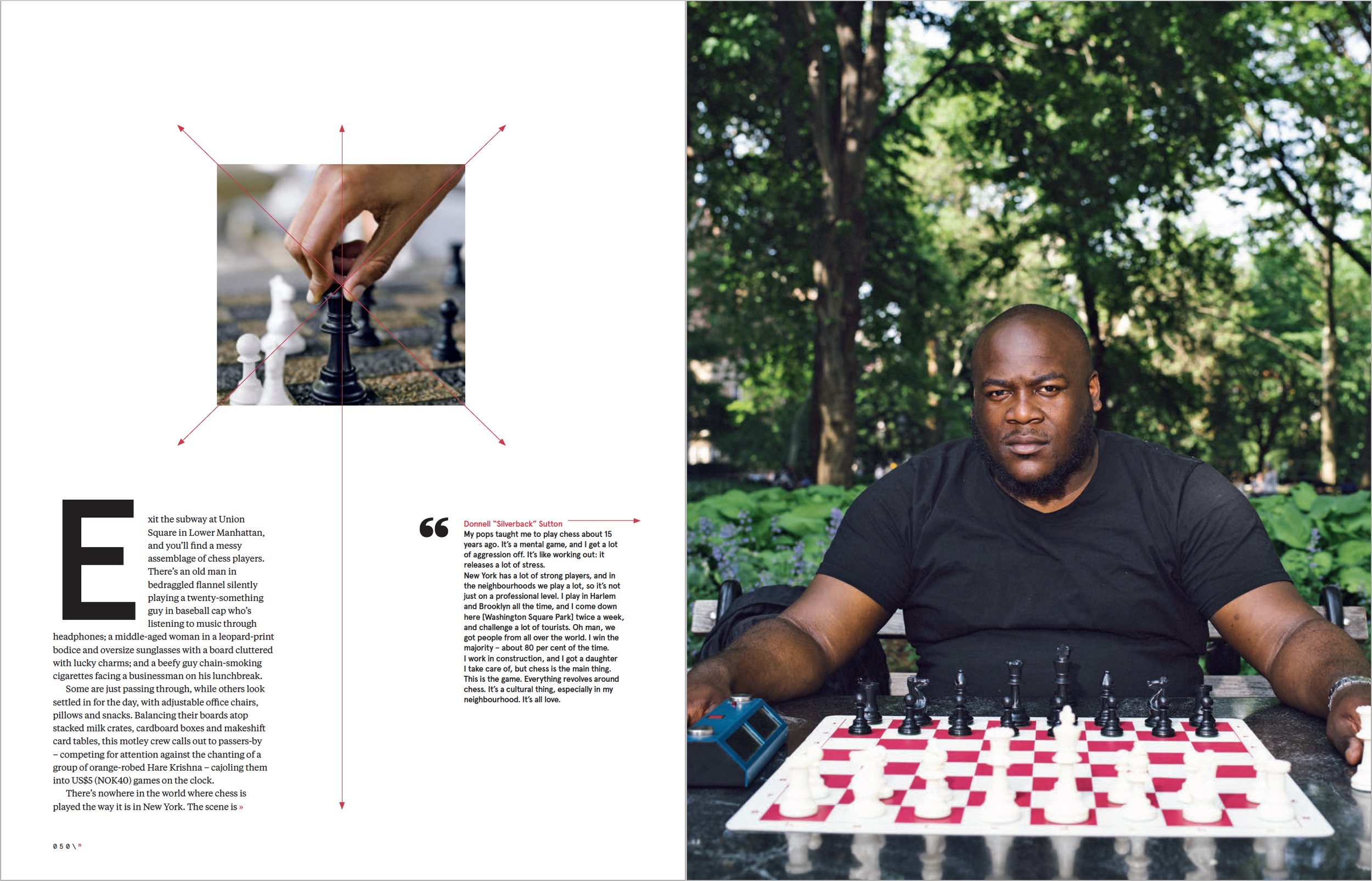

The regulars – like David Ramer, Donnell Sutton and Luis Gonzalez, who usually play at a barbershop in Brooklyn but make it down to Washington Square Park a couple of times a week – play each other for fun and glory, but if a passer-by wants to take them on, it’s a $5 wager to be paid by the challenger, winner keeps all. If there’s any kind of instruction or analysis involved, many players will treat the game as a lesson and charge $5 regardless of who wins. Other players – like the tattooed Russian Paul and International Master Yaacov Norowitz – play each other for more serious money, up to $200 (NOK1,610) a game, in front of crowded onlookers.

Alongside the hustlers and the regulars, there are the chess legends who have played at these tables over the years. Bobby Fischer, referred to by many as the greatest player to have ever lived, played at Washington Square Park and the Chess & Checkers House at Central Park before disappearing from the limelight in 1975. A video of Grandmaster Maurice Ashley going undercover to play hustlers went viral earlier this year.

Even the current world number one, Norwegian Magnus Carlsen, has dropped by at Washington Square Park and Central Park’s Chess & Checkers House when he’s in town. “He thought no one knew who he was,” reports Catherine King, who manages the visitor and games centre at the latter.

Chess has exploded in popularity, globally, over the last decade. Between 2009 and 2013 alone, there was a worldwide increase of 37 per cent in open tournaments, and more people now regularly play chess than golf in the US. King attributes this to Carlsen’s appeal to a younger generation.

“He’s caused a great deal of excitement, and it’s wonderful to see a rejuvenation of the sport. These days, we see so many more youngsters and teenagers coming to play our simuls [simultaneous games where a Grandmaster plays up to 30 people at once].”

The most recent simul series, which took place this summer, saw crowds of over 500 gather to see Grandmasters John Fedorowicz and Maxim Dlugy with International Master Rusa Goletiani. “We see people from all over the world here – the game allows visitors to meet locals and play so easily,” says King. “Chess seems to be a universal language.”

It’s a language that New York’s chess players are keen to spread. “If you see a game of chess and you don’t know how to play, it can be intimidating,” says Michael Propper. “But if you do know how to play, it’s a really exciting game – there’s pressure, stress and adrenaline that you would never dream of. That’s why everyone should play chess – there’s a magic to it.”

Donnell “Silverback” Sutton

“My pops taught me to play chess about 15 years ago. It’s a mental game, and I get a lot of aggression off. It’s like working out: it releases a lot of stress. New York has a lot of strong players, and in the neighbourhoods we play a lot, so it’s not just on a professional level. I play in Harlem and Brooklyn all the time, and I come down here [Washington Square Park] twice a week, and challenge a lot of tourists. Oh man, we got people from all over the world. I win the majority – about 80 per cent of the time. I work in construction, and I got a daughter I take care of, but chess is the main thing. This is the game. Everything revolves around chess. It’s a cultural thing, especially in my neighbourhood. It’s all love.”

Yaacov Norowitz

“I’m an International Master, and I’ve been playing since I was nine. Last year, I was the Jersey champion, and I’d say I’m number two in the country for speed chess. I was brought up in a very strict Jewish culture – at one point I was even training to be a rabbi – so it’s not that easy for me to attend Norm events [a FIDE requirement to achieve titles such as International Master or Grand Master]. They run through the Sabbath, and you have to bring your own kosher food or starve. The parks in New York are great for playing chess – it’s a different culture to the tournaments that I play. You have to have a deep understanding of the game for speed chess, a sense of the fl ow. The less you care, the better. I used to play on the clock in the parks. I would take 30 seconds or a minute to an opponent’s five minutes for $5 a game. I’ve never lost.”

Matthew Laufer

“I was an elementary-school teacher, and then an English tutor. I’m also a poet, but I’ve not made a world of money from that. My father taught me the moves for chess when I was nine, but he proceeded to beat me by 15 games out of 15 games. So I quit. I played my first game at these tables when I was 16, in 1965. I started coming back last year, after four years of trying to pick up games in a random park in Riverdale in the Bronx, where I live. I get more games here, with many different types of people and levels of players. I played a seven-year-old boy from India about three months ago. He wasn’t good, but his 10-year-old sister knew how to play reasonably. If it’s a game, it’s free. If it’s a lesson, that’s work and you have to pay.”

Anthony “Cheese” Koziklowski

“I started playing chess when I was four. My dad taught me how the pieces move, and then I studied on my own and learnt a lot in the parks. My wife is a doctor. We met when she brought her kid to get chess lessons with me. Now, there’s a baby. I normally go to Union Square, but I had a problem there a little while ago so I didn’t want to take the baby there. I charge people $3-5 on the clock. I’ll beat them and I’ll tell them why I beat them, so it’s a lesson. Stronger players don’t necessarily want that. They just want to gamble. I used to hate the analogies that people made between chess and life. Then I started teaching meditation, and realised that the game mimics the cosmic template. In many ways, playing chess is like studying the whole universe.”

Andrea Botero

“I grew up playing chess in Colombia, my home country. I used to win prizes and championships. I quit while I was at university, but then took it back up when I finished. I’ve been playing here at Union Square three times a week since I started working in New York. There aren’t many women who play down here, but it doesn’t bother me. I’ve always been used to that – in chess, in my career. People are often curious. On Friday night, I was down here drinking and playing chess with the guys, and people were like, ‘Go have some fun!’ But I am having fun. Chess has given me so many things: independence, the capacity to solve problems… it’s very useful for life. I love chess, I cannot think of my life without it.”