Paper Visual Art Journal

Volume 09

Suzuki of the Souks

The atelier of artist Eric van Hove, on the dusty outskirts of Marrakech, Morocco, might be described as a motorcycle factory, but it's unlike any other on the planet.

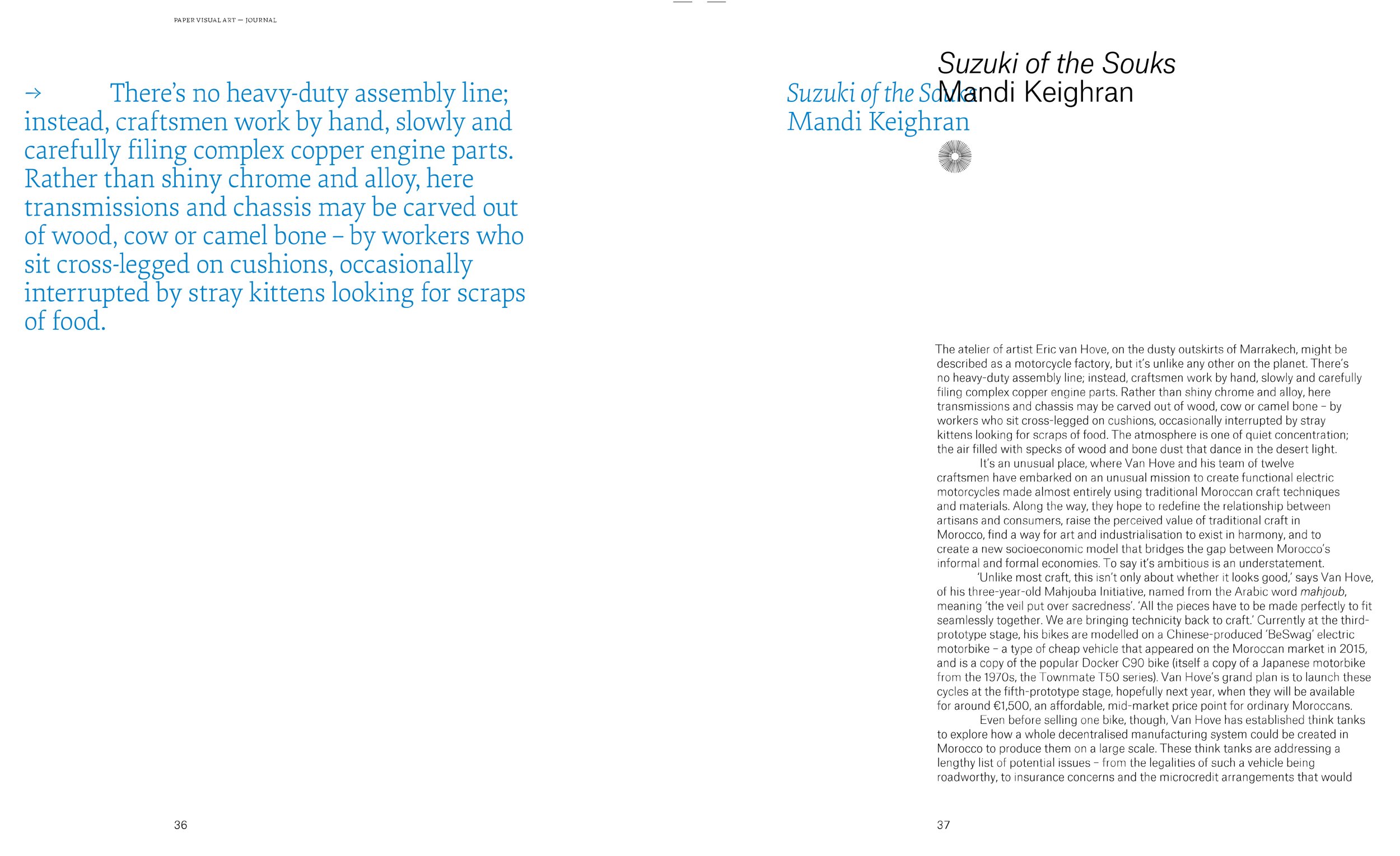

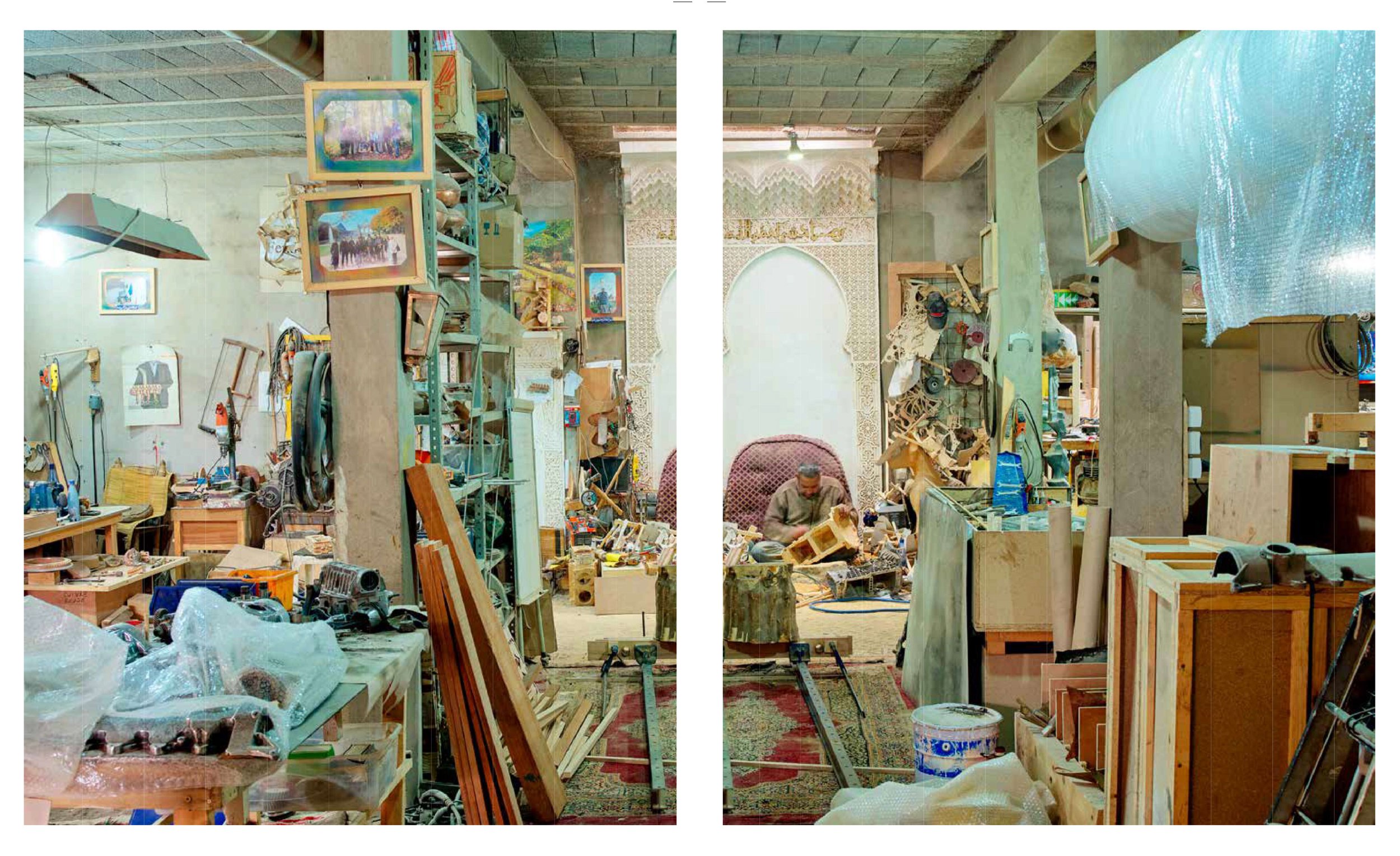

The atelier of artist Eric van Hove, on the dusty outskirts of Marrakech, might be described as a motorcycle factory, but it's unlike any other on the planet. There's no heavy-duty assembly line; instead, craftsmen work by hand, slowly and carefully filing complex copper engine parts. Rather than shiny chrome and alloy, here transmissions and chassis may be carved out of wood, cow or camel bone - by workers who sit cross-legged on cushions, occasionally interrupted by stray kittens looking for scraps of food. The atmosphere is one of quiet concentration; the air filled with specks of wood and bone dust that dance in the desert light.

It's an unusual place, where Van Hove and his team of twelve craftsmen have embarked on an unusual mission to create functional electric motorcycles made almost entirely using traditional Moroccan craft techniques and materials. Along the way, they hope to redefine the relationship between artisans and consumers, raise the perceived value of traditional craft in Morocco, find a way for art and industrialisation to exist in harmony, and to create a new socioeconomic model that bridges the gap between Morocco's informal and formal economies. To say it's ambitious is an understatement.

'Unlike most craft, this isn't only about whether it looks good,' says Van Hove, of his three-year-old Mahjouba Initiative, named from the Arabic word mahjoub, meaning 'the veil put over sacredness'. 'All the pieces have to be made perfectly to fit seamlessly together. We are bringing technicity back to craft.' Currently at the thirdprototype stage, his bikes are modelled on a Chinese-produced 'BeSwag' electric motorbike - a type of cheap vehicle that appeared on the Moroccan market in 2015, and is a copy of the popular Docker C90 bike (itself a copy of a Japanese motorbike from the 1970s, the Town mate T50 series). Van Hove's grand plan is to launch these cycles at the fifth-prototype stage, hopefully next year, when they will be available for around €1,500, an affordable, mid-market price point for ordinary Moroccans.

Even before selling one bike, though, Van Hove has established think tanks to explore how a whole decentralised manufacturing system could be created in Morocco to produce them on a large scale. These think tanks are addressing a lengthy list of potential issues - from the legalities of such a vehicle being roadworthy, to insurance concerns and the microcredit arrangements that would likely need to be agreed with banks to finance local consumption of the bikes -even an app for ordering individually crafted parts.

The vast scale of the project doesn't faze Van Hove. 'It has the potential to transform this whole continent,' he says, of MahJouba. 'Enormous projects like this are more rewarding and meaningful for everybody.'

His ease with thinking on a global scale might be thanks to his nomadic background. Born in Algeria in 1975 to engineer parents, he spent his childhood in Cameroon before relocating to Belgium for schooling at the age of twelve. As a result of this itinerate childhood, his identity was formed through an understanding of himself as an outsider. 'I tried to be Belgian, but it didn't work for many reasons,' he remembers. 'Part of my definition of myself came from being a foreigner. If I couldn't be a foreigner, I was lost.'

This outsider status has guided his career as a creator, first studying contemporary art at the Ecole de recherche graphique in Brussels, and then an art scholarship to study calligraphy and later a PhD in Tokyo - 'I chose Japan because it was the farthest place I could go,' he remembers. Since then he's visited between ninety and one hundred countries - producing ephemeral artworks, encompassing performance, video, photography, sculpture, and writing.

It was only in 2011 that he felt a calling to return to Africa, to begin using his specialist knowledge and develop relationships. While settling down in Marrakech, he found himself intrigued by the proliferation and diversity of artisans. An estimated three million people - 20 percent of the active workforce - are involved in craft in some way.

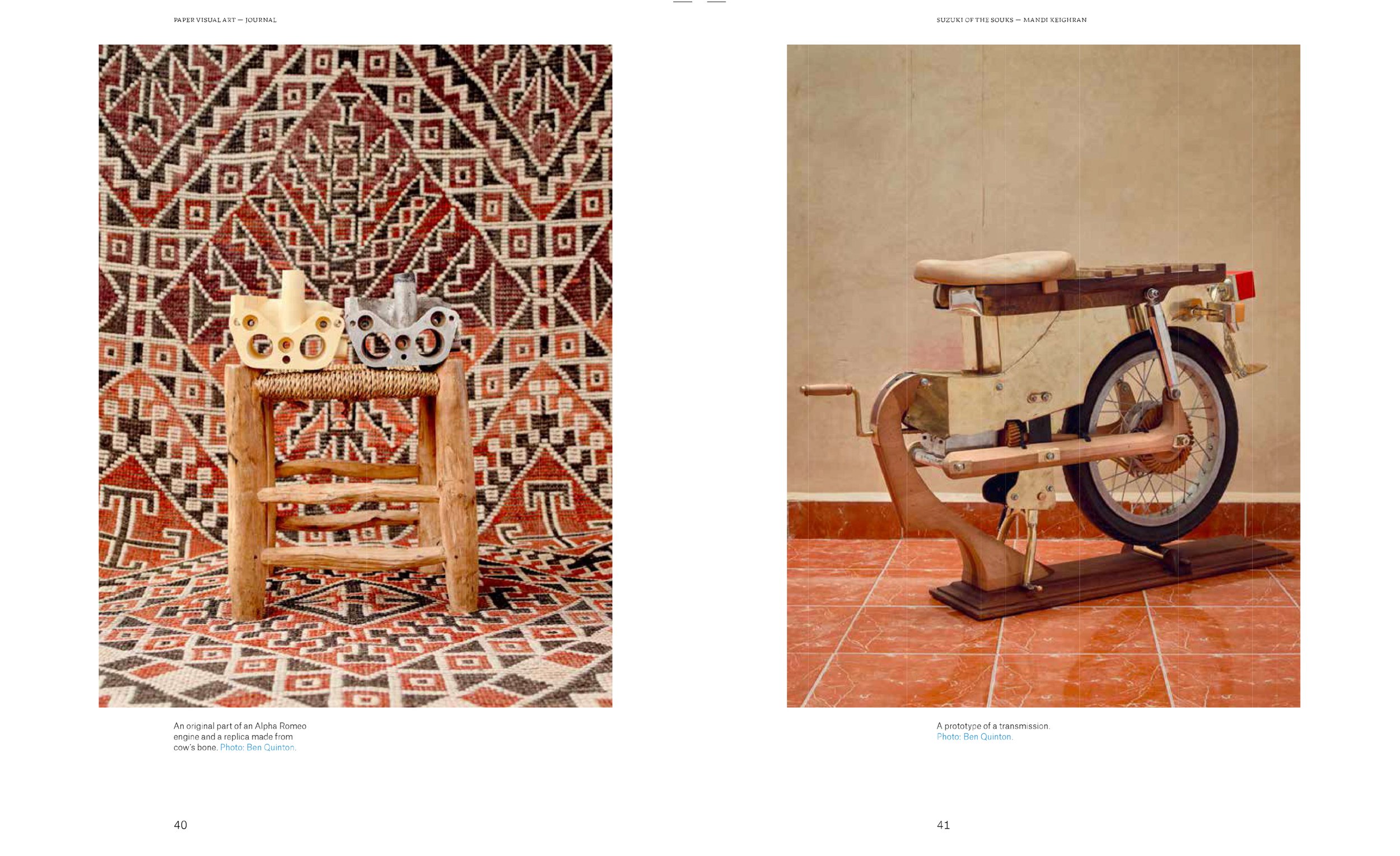

He wondered how this informal economy could find relevance in the twenty-first century. Initially his answer was to create an exact piece-by-piece replica of a Mercedes-Benz 6.0L V12 supercar engine using Moroccan craft techniques and materials. 'It was about questioning the heritage of engineering, and reinterpreting it through the craft legacy,' he says.

It took two years to raise the €20,000 necessary to begin the project, and nine months to find the fifty-seven artisans who eventually completed the engine. The result, titled V12 Laraki (2013) in reference to the Laraki Fulgura – a supercar built by Moroccan company Laraki in which everything is made in Morocco except the engine – is a surreal sight.

The behemoth comprises 465 precisely handcrafted pieces that employ fifty-three different craft techniques, from embroidery and weaving to bone inlay and timber carving. Astonishingly, when it's assembled, almost 80 percent of these meticulously honed parts are hidden. 'Once it was assembled, it was a fantastic thing,' says Van Hove. 'If you do something like that, it changes your life, and I saw the potential of the craft sector.' He set about establishing his atelier with a team of artisans. 'It's very diverse - from Berber craftsmen from the mountains to an ex-competitive kickboxer from the Medina.'

The idea for the bikes came in 2016, when Marrakech was hosting a summit on climate change, and it had just been announced that the country aims to have 42 percent renewable energy consumption by 2020. He happened to see a BeSwag driving past one day: his eureka moment.

Aside from the practical application, he hopes that Mahjouba will create a renewed appreciation for craft skills that have been gradually disappearing over the past twenty years, as tourists have replaced Moroccans as the primary consumers of locally crafted goods. 'It's important to bring value back to these skills and also local clients who are actually using the products,' he says.

Although global success seems a long way away at this stage, we live in a world where craft economies are burgeoning in areas from food to fashion. It's pleasing to think that expert craftsmanship might achieve a wider application in mechanics, too. Van Hove is certainly upbeat about the prospect, but for him it seems that the journey is as important as the destination. 'Obviously, it might fail in so many ways,' he says. 'But ... what if? That's the beautiful thing about art - it can fail and it still might be a success.'